Abandon Ship!

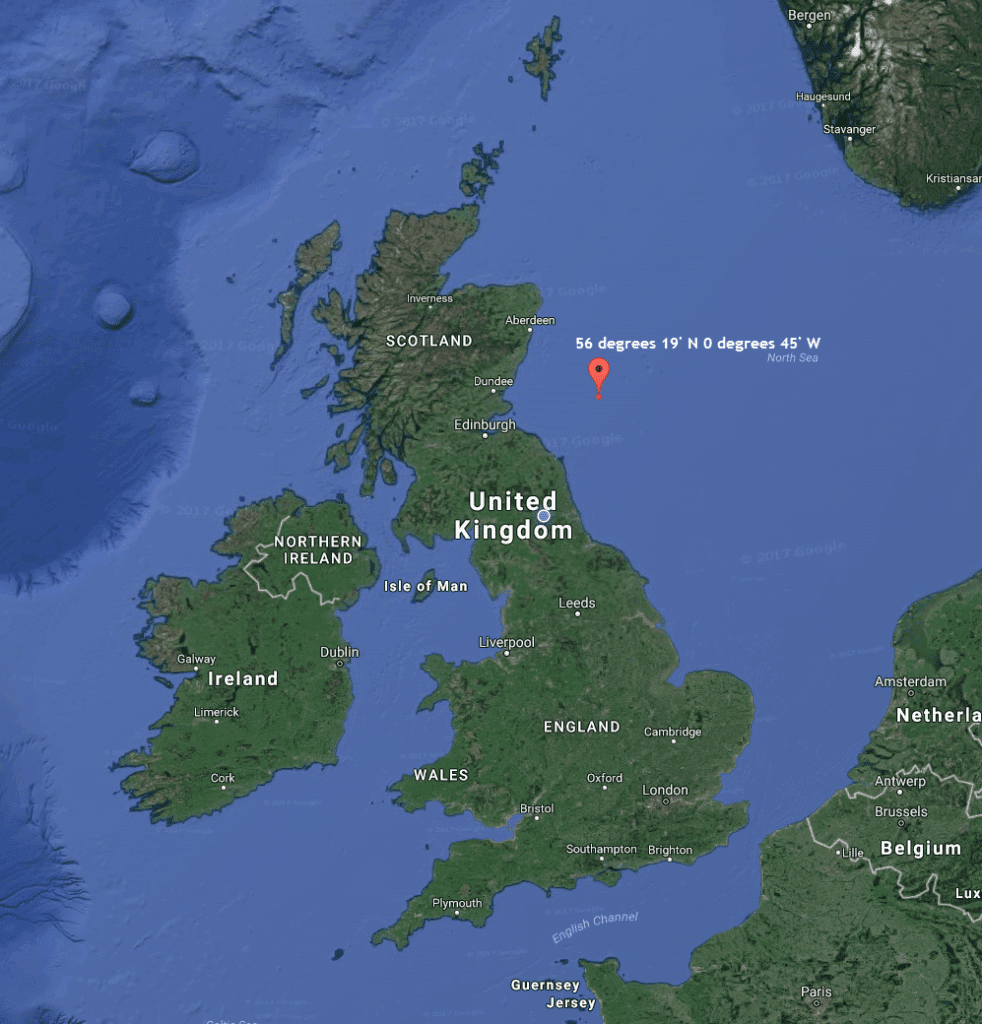

This was the order that Lt James Kennedy, commander of the HM Whaler ‘Blackwhale’ had to give on the night of 3rd January 1918 after his convoy escort ship hit a mine off East Fife Ness at the position shown on the map.

James wasn’t on watch at the time. According to the official report on the incident carried out by the Admiralty, at 3:45 AM after a course change ordered by the convoy force commander, Office of the Watch James Nair (2nd Hand) spotted:

… a black object right under his port bow. An explosion immediately followed, resulting in the fore part being submerged and in her eventually sinking, after remaining afloat for about two and a half hours.

Twelve men lost their lives. Of these two are known to have been drowned from the raft. The other ten were watch below engine room ratings, and it appears they were asleep on their mess-deck at the time. As this mess-deck is right forward and in the immediate vicinity of the scene of the explosions, there can be no doubt that they were killed by the shock or drowned, when her fore part submerged.

Of the crew saved ten men left the ship in the starboard lifeboat and were picked by Swedish SS “Ethel”. That they left the ship without orders is due to the boat breaking adrift. the remaining nine left the ship, some in the port lifeboat and others on the raft, and were eventually picked up by HM Trawler “Grosbeak”.

Lieutenant Kennedy was the last to leave the ship and kept himself afloat on a ladder till picked up by “Grosbeak.”

The Official Report

The North Sea in early January, in the dark of night, must have been a cold, frightening and hostile environment in which to abandon ship and trust to lifeboats, rafts and a ladder. It’s amazing that anyone survived at all. The official report mentions “... the heavy weather then prevailing“

Kennedy made a statement to the Admiralty about the loss of the Blackwhale.

At 3.45 a.m. on 3rd Jan 1918, the “BLACKWHALE” struck what is supposed a mine. An explosion occurred apparently between No. 1 and 2 mess decks on the starboard side. The ship began to settle down at once. The wireless was put out of action by the explosion, the rotary being in the mess deck, which was flooded.

Signals by morse were flashed to the destroyers, convoys, and apparently understood by all concerned.

Orders were given to lower the boats, and it was reported at the time that nobody was left in the mess deck. After the order was given to lower the boats I went to the bridge before the steam ran off, and repeated the signal by morse on the whistle to prevent any misunderstanding; this message I passed on the whistle, but received no answer.

On my return aft I found one boat had put off without my orders, with, as far as I can ascertain, 20 ratings. The other boat was then lowered to the rail with the 12 remaining men aboard, and three men stepped in it to to guard it. This boat was washed clean away from the tackles with the three men in her about a quarter of an hour after she had been put in that position. We were then left with 9 all told (myself and 8 men). I then again communicated by means of a torch which I found in my cabin to a destroyer that I had no boats and the ship was gradually going down; this signal was answered in the affirmative. A trawler was then seen in the vicinity. We managed to get a coil of 6″ line, the intention being to pass it to the trawler, and for her to hang astern, but apparently the Skipper of the trawler was afraid of coming too near in case of touching the Whaler and causing her to sink immediately, which was quite correct. The trawler then steered dead to windward and lowered a boat, but was unable to assist us owing to it capsizing and his own men being in the water. He took up his men and then steamed down in the direction of the whaler. All this time the ship was gradually going down and she slewed broad wise on the sea and went down immediately

A raft (which was already prepared) with 8 ratings aboard on the aft gun platform was launched and the men ordered to take to it. The ship sunk. I was the last person to leave her, taking refuge on a broken ladder. I was in some hopes that the vessel having lasted for two and a half hour, (as she finally sunk at 6.15 am) that she might weather the weather until daylight when there would have been the possibility of saving her.

The three men who broke adrift in the boat were picked up by a trawler at once. Six men were saved from the raft; the two lost being:- Alfred Beresford, CERA and Thos. Kirk, Deck Hand

As regards the boat containing the 20 men, I have no further knowledge. I was picked up after the second boat and the men on the raft had been saved, by the same trawler.

I would like to report most favourably on the loyalty and excellent conduct of the following men who remained with me to the last:- Hy, Hoffman, Deck Hand. J. Vince, OS RNCVR. T Kirk, Deck Hand (since drowned). W Lyall, Sea RNR. J Morgan, 2nd Hand. A Beresford, CERA (since drowned) A Carnegie, Deck Hand. D Hall, Signalman\. G Grassie, AB A Burnie, Deck Hand. R Quick, OD RNCVR.

The Flag Captain of the HMS Wallington obviously had some follow-up questions because on the 6th January 1918, James Kennedy wrote a further report:

I was Senior Office in charge of Escort Force “R”, the following vessels comprising the force:- Blackwhale; Venator; Imperia; Huxley; Phyllis Belman; Inchkeith; Othello; Grosbeak, the Destroyers Ness, Ouse and Teviot accompanying.

At the time of the explosion, the course was N 48 E magnetic, average speed 4 knots, wind NE force 6 to 7. sea rough.

The approximate position when an explosion occurred was 56-19 N, 0-45 W.

I was leading the convoy at the time, being about a mile ahead of the leading ship of the convoy. All I saw at the time was apparently a destroyer on my starboard quarter and what appeared to be a destroyer on my starboard bow, no other vessels beyond those referred to being in sight.

I was below resting at the time, James Nair, Second Hand, being on the bridge; Andrew Carnegie, Deck Hand at the wheel; Roy Quick, AB, RNCVR, in crow’s nest; Gilbert Jamieson, Seaman RNR, at the gun aft and Albert Howard, Deck Hand Signalman on the bridge,

The confidential books etc were locked in the weighted chest an all sank with the ship. [There is a left margin hand-written note: “Confirmed 31.1.18”]

Looking at this through 21st-century eyes, it seems extraordinary that someone with the rank of Lieutenant should be be in command of eight ships!

Lieutenant James Kennedy RNR OBE (Mil)

So who is Lieutenant James Kennedy RNR OBE (Mil) and how does he feature in our family tree?

Well, he is not a blood relation for a start so his story is almost peripheral to our family history. But it’s such a good story that it needs telling.

In 2005 when some investigations were going on into the family history, Lieutenant Kennedy was something of an enigma. We knew very little about him, other than he was our mother’s Great Uncle by marriage. (He married the sister of Mum’s grandfather’s wife, Jane Harris. We had no photos and no certified information as to his birth, marriage or death, although I did find his marriage certificate in May 2006 and his death certificate in June 2013. They were married on the 21st Dec 1912, when he was 41 and she 43. He died on 15th Jan 1944 at the age of 73 of throat cancer.

However, we have some physical evidence; a set of World War I campaign medals, all engraved with his rank and name, an OBE (Mil) and a gold pocket watch. These items were left to me by my grandfather Henry James Howell, who had inherited them on the death of James. He was childless and, as far we can tell, had no siblings nor other family members.

The watch has always intrigued me because whilst coming from H. Samuel (a High Street jeweller of little distinction today) it is nicely engraved with James’ initials, and has a gold chain that is in some ways more interesting (certainly far more valuable) than the watch itself. When it was passed on to me the watch was not working, the winder having been broken. However, I had it restored to working order in the 1970’s and it remains in full working order today. It is complete with a leather pouch. Whether this is contemporary with the watch is unknown, but it was with the watch when it was passed to me in the 1960’s.

In 1993 the watch and chain were valued at £1,225 and, as the movement is unexceptional, its value is largely the result of the gold content. If we assume its value in 1913 (the approximate date of its manufacture according to the 1993 valuer) was also linked to the price of gold then, by any standard, the person who owned must have had a degree of affluence. And that, together with the OBE (Mil) meant that we needed to investigate him.

Attempts to trace his birth proved impossible because we had no clues as to when or where it took place and his name is so common that a search through all the entries was impractical.[/toggle]

Childhood Memories of James by Mary Abbs

We had one advantage when conducting our research – a then living relative. Our aunt, Mary Abbs, now departed, had clear recollections of her Great Uncle.

[My Great] Aunt’s name was Jane but known to us as Aunt Jinny. She had no children as she married late in life to a naval officer who actually was a Captain* and he was Captain* James Kennedy OBE, awarded for bravery during WWI.

Mary meant Captain in the sense that he commanded the vessel he was assigned to. His actual rank was Lieutenant. “Jane” was actually “Harriet Jane”

Letter 29th Mar 2005:

He was a very interesting man as his father served for some years as Governor of Mauritius Island where he grew up. They (James and Jane) were like grandparents to us and always came to stay at Easter and Christmas. Etc. Nanny Howell visited them a lot when they lived in London. I vaguely remember going with her to Forest Gate (London) to a big house, with lots of big heavy curtains between each room. They only lived upstairs. Then, when got older, Nanny got them a bungalow in Corwell Lane, Hillingdon so that she could help look after them as Uncle was then rather ill. He was a very jolly man and used to tell us all kinds of stories about his childhood and his adventures at sea.

Letter 1st May 2005:

He was sent to sea as a cabin boy at an early age and stayed in the Navy until he retired. He was awarded the OBE for bravery in the First World War, and his ship was sunk by a gunboat. He was captured as he stayed on the bridge which was the rule, ‘The Captain must never leave his ship.’ He was dumped ashore somewhere very remote but was rescued by fishermen. At least this is what I remember him telling us. But he was a great one for ‘spinning a yarn’ as he used to call his stories.

As regards to when or where he married Aunt Jane (Jinny) I don’t know. But she talked about meeting him at Peterhead (North of England I think.) They used to have parties for Officers and their wives etc. But how they ended up in Forest Gate I don’t know.

Uncle Jim did have a brother who was in the Army and lived in Salisbury after his retirement but I can’t remember his Christian name”

What can we Verify?

As Mary herself suggested, some of these ‘facts’ may have grown in the telling and having investigated as much as I can, I think that is very likely. But then two impressionable young great nieces would have been an excellent audience for exciting tales of derring-do, so who can blame him if a little embellishment took place?

First of all, I looked into the reported link to Mauritius. There was no governor called Kennedy in the 1800’s. In fact, no Kennedy appears until the 1940’s, far too late. I suppose it is feasible that the Kennedy family was employed in some more junior position and the rank of his father was exaggerated in the telling, but if this is the case there is now way of telling. Another, remote, possibility is that he was indeed the son of the governor, but that it was the result of a dalliance between the governor and James’ mother. It’d make a good romantic novel.

Governors

4 Dec 1810 – 20 May 1823 Robert Townsend Farquhar (b. 1776 – d. 1830) (from 1821, Sir Robert Townsend Farquhar)

18 Apr 1811 – 15 Jul 1811 Henry Warde (acting for Farquhar) (b. 1766 – d. 1834)

19 Nov 1817 – 1818 Gage Hall (acting for Farquhar)

1818 – 1819 John Dalrymple (acting for Farquhar)

Feb 1819 – 5 Jul 1820 Ralph Darling (acting for Farquhar)(b. 1772 – d. 1858)

1820 – 1828 Sir Galbraith Lowry Cole (b. 1772 – d. 1842) (acting for Farquhar to 1823)

1828 – 1833 Sir Charles Colville (b. 1770 – d. 1843)

1833 – Feb 1840 Sir William Nicolay (b. 1771 – d. 1842)

1840 – 1842 Sir Lionel Smith (b. 1778 – d. 1842)

1842 – 1849 Sir William Maynard Gomm (b. 1784 – d. 1875)

1849 – 1851 Sir George William Anderson (b. 1791 – d. 1857)

1851 – 1857 Sir James Macaulay Higginson (b. 1805 – d. 1885)

1857 – 1863 Sir William Stevenson

1863 – 1871 Sir Henry Barkly (b. 1815 – d. 1898)

1871 – 1874 Arthur Charles Hamilton-Gordon (b. 1829 – d. 1912)

1874 – 1879 Sir Arthur Purves Phayre (b. 1812 – d. 1885)

1879 – 1880 Sir George Ferguson Bowen (b. 1821 – d. 1899)

1880 – 1883 Sir Frederick Napier Broome (b. 1842 – d. 1896)

1883 – 1889 Sir John Pope Hennessy (b. 1834 – d. 1891)

1889 – 1893 Sir Charles Cameron Lees (b. 1831 – d. 1898)

1893 – 1897 Sir Hubert Edward Henry Jerningham (b. 1842 – d. 1914)

1897 – 20 Aug 1904 Sir Charles Bruce (b. 1836 – d. 1920)

20 Aug 1904 – 13 Nov 1911 Sir Cavendish Boyle (b. 1849 – d. 1916)

13 Nov 1911 – 18 May 1916 John Robert Chancellor (b. 1870 – d. 1952) (from 1913, Sir John Robert Chancellor)

18 May 1916 – 19 Feb 1925 Sir Henry Hesketh Joudou Bell (b. 1864 – d. 1952)

19 Feb 1925 – 30 Aug 1930 Sir Herbert James Read (b. 1863 – d. 1949)

30 Aug 1930 – 21 Oct 1937 Wilfrid Edward Francis Jackson (b. 1883 – d. 1971) (from 1931, Sir Wilfrid Edward Francis Jackson)

21 Oct 1937 – 5 Jul 1942 Sir Bede Edward Hugh Clifford (b. 1890 – d. 1969)

5 Jul 1942 – 26 Sep 1949 Sir Donald Mackenzie-Kennedy (b. 1889 – d. 1965)

So, we see the name Kennedy, finally, in 1942 but this is far too late to bring any credibility to the story.

His War Medals and the Award of the OBE (Mil)

Having drawn a blank on his links to Mauritius I decided to focus on something more tangible – his military service record, in particular, the award of the OBE (Mil). Aunty Mary said this was awarded for bravery during WWI. In fact the notice published in the London Gazette on 27th Jun 1919 cited ‘valuable services’ whatever that may mean.

In the photograph

The OBE is the medal on the left. The rest of the medals are WWI campaign medals. Unfortunately, an Oak Leaf addition to the medal on the right has become lost. An impression is present on the medal ribbon but the oak leaf itself is missing.

In addition to the full-size set shown in the first photograph, I also inherited a set of miniatures. Apparently, miniatures are worn after sunset for Mess or other official evening events. You can see that the Oak Leaf is present on the miniature.

The miniatures also feature something that has never been present on the full-size medals, a set of six bars to the medal second from the right which state ‘North Sea’ and are dated 1914, 1915, 1916, 1917, 1918 and 1918-19 respectively. The miniature set doesn’t have the OBE. I don’t know whether it ever existed – the medal bar was clearly designed to include it, but it was not present when the medals were passed to me.

The miniatures are sitting in a case that is not designed for them – the case in which the OBE (Mil) medal was presented to James Kennedy. Clearly, he transferred the OBE to a larger medal pin so he could wear it with his others.

You get a good sense of the scale of the miniature set from the fact that they fit inside the OBE case. In fact, that is what the OBE case is used for – to store the miniatures. It’s battered and worn, and it was in that condition when it was handed down to me. I cannot believe that my Grandfather would have treated it badly so we have to assume that, in his lifetime, James Kennedy used it well. He was a navy man all his life and perhaps he carried it with him at sea as a reminder of his contribution in the First World War. Who knows?

The OBE (Mil) Award Notice

Based on the hard evidence of the medal, I carried out an Internet search for information about the honours systems, and links on the Cabinet Office site lead me to the London Gazette, which has an online archive. A search for James Kennedy soon revealed an entry dated 27th June 1919 announcing the award of the OBE.

Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood, St James Palace SW. 27th June 1919

The KING has been graciously pleased to give orders for the following promotions in and appointments to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, in recognition of the undermentioned Officers during the war:-

To be Officers of the Military Division of the said Most Excellent Order:-

Lieutenant James Kennedy R.N.R.

For valuable services in command of H.M. Whaler ‘Blackwhale’ whilst acting as leader of Coastal Convoys.

It was for ‘valuable services’ rather than bravery. That’s not to say he wasn’t a brave man. I am absolutely positive that all the sailors who served in the coastal convoys routinely performed tasks that we would not countenance doing today. But the military had specific medals for bravery. The OBE was awarded for exceptional service over a long time. Not that many were awarded so it must have been a great honour for him.

HM Whaler ‘Blackwhale’

The award announcement brings us back to the ship that he commanded, HM Whaler, ‘Blackwhale.’ An internet search for ‘Blackwhale’ brought me to an online forum http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/ dedicated to the Great War from which I was able to obtain a surprising amount of information, with relative ease.

HM Whaler BLACKWHALE Number Z.5, Admiralty Number 868.

These whalers were ordered 15th March 1915 and were all built by Smiths Dock Co using designs prepared for the Russian Government. The expected manoeuvrability of these vessels made them suitable for anti-submarine escorts in coastal waters. They were originally numbered Z 1 – 15, names came later. The first vessel was completed in June 1915. Their performance in heavy weather was less than comparable trawlers and the design was not repeated in future orders.They were 237 tons gross, 125 x 25 x 8.5 feet, 1200 bhp giving 13 knots and armed with 1 x 12 pounder. HM Whaler Blackwhale was launched 28th June 1915 and was lost when she struck a mine off Fife Ness on 3rd January 1918.

These whalers served in three squadrons, one based Stornoway, one at the Shetlands and one at Peterhead or the Humber. From the information and position of the loss she would most likely be in the latter squadron between Peterhead, Aberdeenshire and the Humber.

Dittmar and Colledge give Escort Duties as the sole role. They do not mention minesweeping for which the Navy usually used trawlers or drifters. Tom [Kirk] may have been a fisherman before the war and joined the RNVR. Most smaller auxiliary vessels would be manned by RNR men perhaps with regular officers on some.

It seems the squadron was based sometimes at Peterhead and sometimes at the Humber (Hull?) which suggests escort in the North Sea coastal waters. Mines were always being dropped by U Boats off the mouth of the Forth to try to sink one of the Battleships of the Grand Fleet based at Rosyth.

Here is a picture of the sister ship the whaler Meg.

One contributor told me that Blackwhale sank on a mine laid by the German mine-laying submarine UC 49 on December 10, 1917. I was intrigued by the accuracy of that information and asked how it was possible to be so certain.

If you have a location and a date of a sinking, it’s quite possible to work out which U-boat laid the mine and when, by looking at the U-boat’s KTBs (Kriegstagebücher = war diaries, yes they survive). The amount of mine-laying along the Scottish coast is ultimately rather finite — the Flanders-based boats didn’t operate that far north which reduces the possibilities considerably.

The attribution in this case ultimately comes from the German official history series Handelskrieg mit U-Booten by Admiral Arno Spindler. Spindler and his team spent many years working through the available information to determine, as best as possible, exactly which U-boats sank what.

In regard to the crew, twelve ratings were lost in the sinking of the ship. No officers or 2nd Hands were killed.

Edit 2 May 2017: We know when and where Blackwhale was built – and it was not far from where she sank – thanks to the wreckksite.eu

One other piece of valuable information from the Great War Forum was that his [naval] records are at Kew, in ADM 240. So we have a potential line of enquiry to follow up here, one that may unlock some information about his date of birth, home town etc. That would help us prove or disprove some of the family legends. Unfortunately, it appears that at least one of those is in the realms of fantasy.

He was awarded the OBE for bravery in the First World War, and his ship was sunk by a gunboat. He was captured as he stayed on the bridge which was the rule, ‘The Captain must never leave his ship.’” [so far so good] “He was dumped ashore somewhere very remote but was rescued by fishermen.*†[A great sea story]

Mary Abbs

† The ship that rescued him was a trawler. It’s possible that James constructed a story from that fact, or maybe the girls did.

To be resolved…

Unresolved issues include:

- Family legend says “he was apprenticed as a cabin boy.” Now we are in the realms of Gilbert & Sullivan! I find it hard to reconcile that with the other legend that his father was the Governor of Mauritius, but then, if his father was not… ?

- Will his naval records give us any information about his birth or hometown?

- He was formally listed as RNR, Royal Naval Reserve. That does not seem to fit well with the idea that he was in the (Royal) Navy from cabin boy to retirement. As I understand it, members of the Royal Naval Reserve were former members who, having left the Royal Navy, could be called up at times of need, such as the Great War. After a spell in the Royal Navy was he, in fact, a Merchant Navy man? Did he return to that after the war?

So there we have it – the story of Lt. James Kennedy, as far as we know it.

Paul Barrett

Footnote:

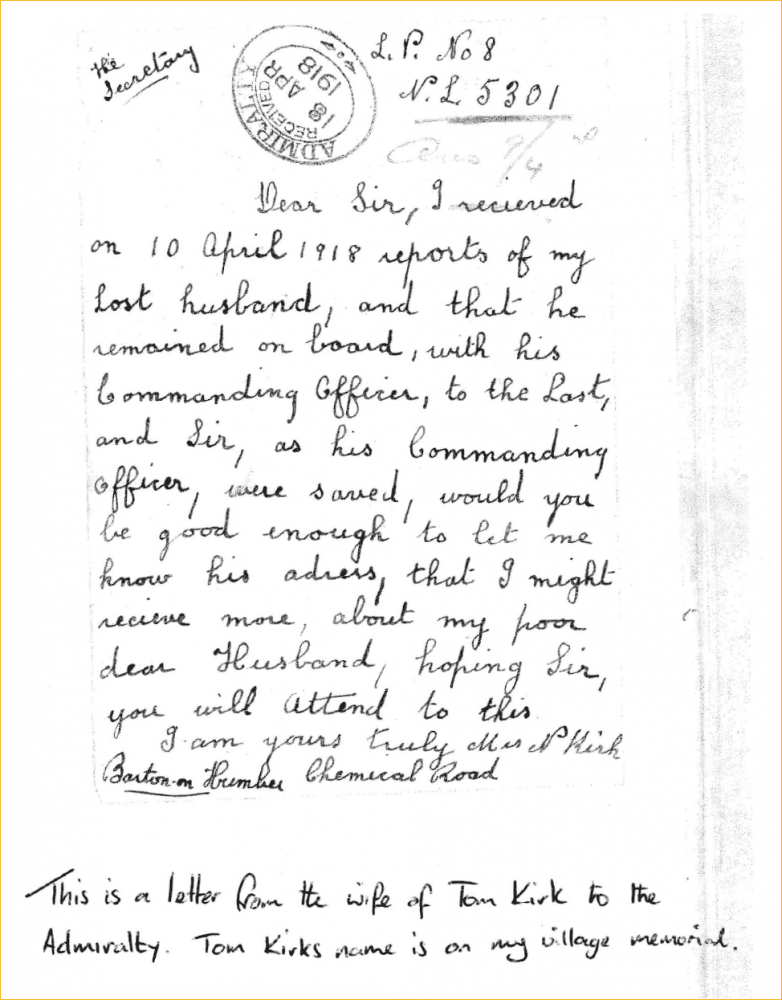

One of the documents provided to me by one of the Great War Forum members was this touching letter from the widow of one of the casualties, Tom Kirk, and the Admiralty’s reply.

Letter from widow of Tom Kirk to the Admiralty

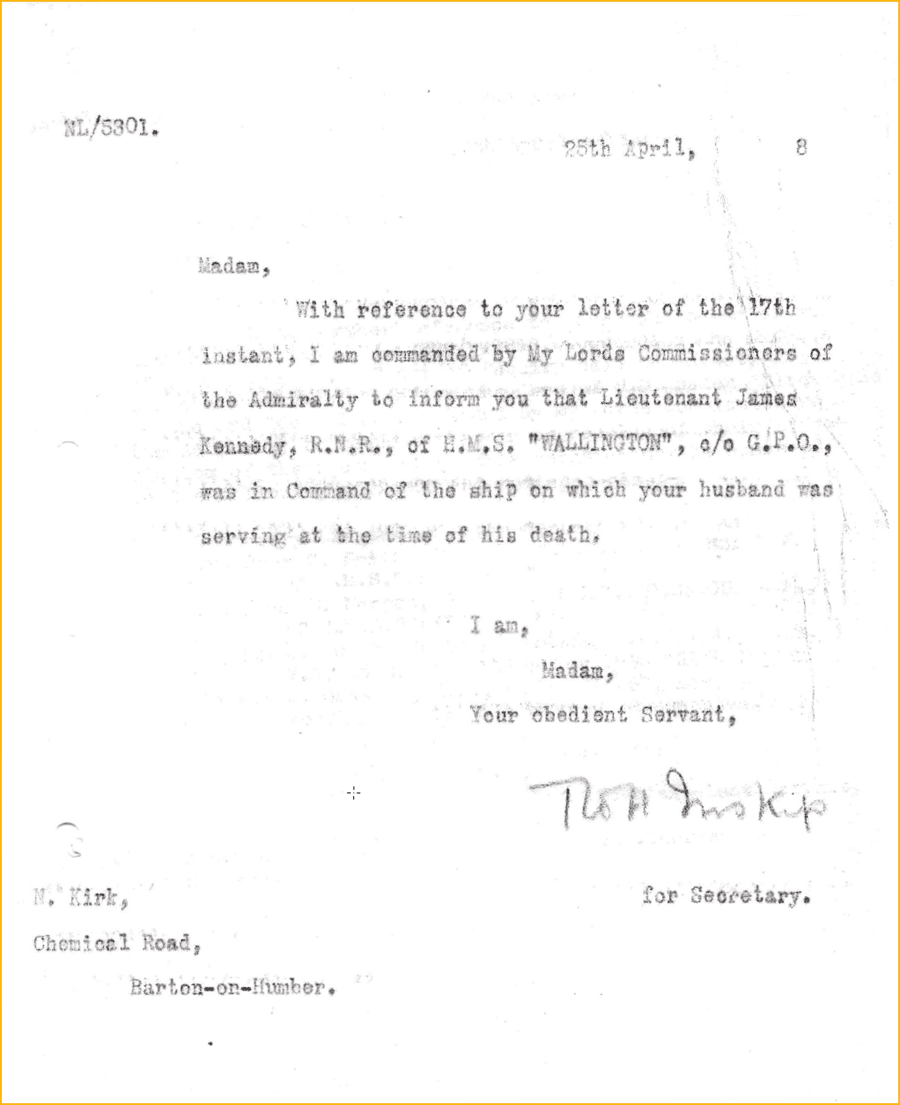

Admiralty reply to Tom Kirk’s widow.

I don’t know whether the widow wrote to James Kennedy or he replied.

20th March 2017