| |

Date |

Event(s) |

| 1 | 1702 | - 8 Mar 1702—1 Aug 1714: Queen Anne's reign

Queen Anne, the second daughter of James II, Anne was a staunch, high church Protestant. During her reign Britain became a major military power and the foundations were laid for the 18th century’s Golden Age.

Anne was plagued by ill health throughout her life, and from her thirties, she grew increasingly ill and obese. Despite seventeen pregnancies by her husband, Prince George of Denmark, she died without surviving issue and was the last monarch of the House of Stuart. Under the Act of Settlement 1701, which excluded all Catholics, she was succeeded by her second cousin George I of the House of Hanover.

|

| 2 | 1704 | - 4 Aug 1704: Gibraltar captured

Anglo-Dutch forces captured Gibraltar from Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession on behalf of the Habsburg claim to the Spanish throne. The territory was ceded to Great Britain in perpetuity under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. During World War II it was an important base for the Royal Navy as it controlled the entrance and exit to the Mediterranean Sea, which is only 8 miles wide at this naval choke point.

Anglo-Dutch forces captured Gibraltar from Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession on behalf of the Habsburg claim to the Spanish throne. The territory was ceded to Great Britain in perpetuity under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. During World War II it was an important base for the Royal Navy as it controlled the entrance and exit to the Mediterranean Sea, which is only 8 miles wide at this naval choke point.

The sovereignty of Gibraltar is a point of contention in Anglo-Spanish relations because Spain asserts a claim to the territory. Gibraltarians rejected proposals for Spanish sovereignty in a 1967 referendum and, in a 2002 referendum, the idea of shared sovereignty was also rejected.

|

| 3 | 1707 | - 16 Jan 1707: Kingdom of Great Britain founded

Union of England and Scotland. With its economy almost bankrupted following the collapse of the Darien Scheme, a poorly attended Scottish Parliament voted to agree the Union on 16 January

The early years of the unified kingdom were marked by Jacobite risings which ended in defeat for the Stuart cause at Culloden in 1746. In 1763, victory in the Seven Years' War led to the dominance of the British Empire, which was to become the foremost global power for over a century and slowly grew to become the largest empire in history. The Kingdom of Great Britain was replaced by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 1 January 1801 with the Acts of Union 1800

|

| 4 | 1709 | - 1709: Iron making

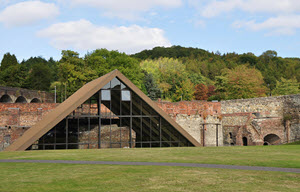

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting.

This is where iron ore was first smelted by Abraham Darby using easily mined "coking coal". The coal was drawn from drift mines in the sides of the valley. As it contained far fewer impurities than normal coal, the iron it produced was of a superior quality. Along with many other industrial developments that were going on in other parts of the country, this discovery was a major factor in the growing industrialisation of Britain, which was to become known as the Industrial Revolution.

|

| 5 | 1714 | - 1 Aug 1714—11 Jun 1727: King George I's reign

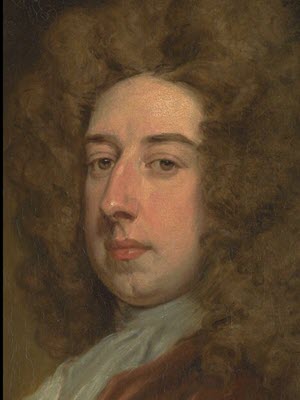

George I ascended the British throne as the first monarch of the House of Hanover. Although over 50 Roman Catholics were closer to his predecessor, Anne by primogeniture, the Act of Settlement 1701 prohibited Catholics from inheriting the British throne; George was Anne's closest living Protestant relative. In reaction, Jacobites attempted to depose George and replace him with Anne's Catholic half-brother, James Francis Edward Stuart, but their attempts failed.

During his reign, the powers of the monarchy diminished and Britain began a transition to the modern system of cabinet government led by a prime minister. Towards the end of his reign, actual political power was held by Robert Walpole, now recognised as Britain's first de facto prime minister. George died of a stroke on a trip to his native Hanover, where he was buried - the last British monarch to be buried outside the UK.

|

| 6 | 1718 | - 1718: Transportation of Convicts Begins

The Transportation Act 1717 introduced penal transportation. People convicted of capital crimes had their sentences commuted to 14 years or life in the Americas. Convicts found guilty of non-capital crimes received seven-year sentences. Between 1718 and 1776, over 50,000 convicts were transported to Virginia and Maryland in the modern United States. The American Revolution made further transportation impossible.

|

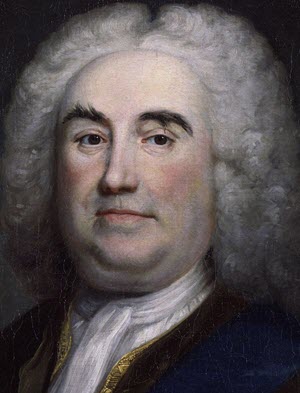

| 7 | 1721 | - 3 Apr 1721—11 Feb 1742: Sir Robert Walpole - 1st British Prime Minister

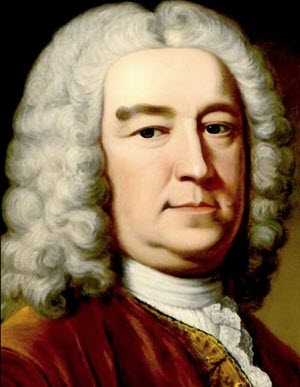

In the wake of the South Sea Bubble financial crisis, Walpole became First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer. He never held the title 'Prime Minister,' but was given the powers that came to be associated with the office. George I also gave him 10 Downing Street, still the official residence of the prime minister.

|

| 8 | 1727 | - 11 Jun 1727—25 Oct 1760: King George II's reign

George IIexercised little control over British domestic policy, which was largely controlled by the Parliament of Great Britain. As elector, he spent twelve summers in Hanover, where he had more direct control over government policy.

During the War of the Austrian Succession, George participated at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743, and thus became the last British monarch to lead an army in battle. In 1745, supporters of the Catholic claimant to the British throne, James Francis Edward Stuart ("The Old Pretender"), led by James's son Charles Edward Stuart ("The Young Pretender" or "Bonnie Prince Charlie"), attempted and failed to depose George in the last of the Jacobite rebellions.

|

| 9 | 1731 | |

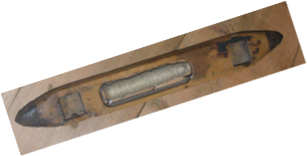

| 10 | 1733 | - 1733: The Flying Shuttle

The flying shuttle was patented by John Kay in 1733. Its adoption would revolutionize the British textile industry and, in no small part, help spark the industrial revolution. Its basic design was improved over the following years with an important one in 1747

- 24 Mar 1733: Joseph Priestley born

Joseph Priestley was a renowned English theologian, author, chemist and political theorist of the 18th century. He is also regarded by many as the one who discovered oxygen. His contribution to science was so immense that he had been made a member of nearly every major scientific society by the time he passed away

|

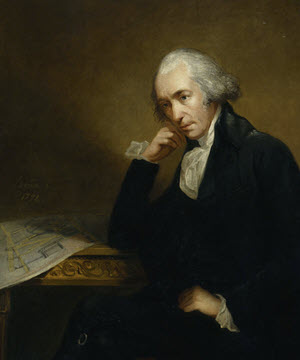

| 11 | 1736 | - 1736: James Watt born

James Watt was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was fundamental to the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution in both his native Great Britain and the rest of the world.

While working as an instrument maker at the University of Glasgow, Watt became interested in the technology of steam engines. He realised that contemporary engine designs wasted a great deal of energy by repeatedly cooling and reheating the cylinder. Watt introduced a design enhancement, the separate condenser, which avoided this waste of energy and radically improved the power, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of steam engines.

Watt attempted to commercialise his invention, but experienced great financial difficulties until he entered a partnership with Matthew Boulton in 1775. The new firm of Boulton and Watt was highly successful and Watt became a wealthy man.

|

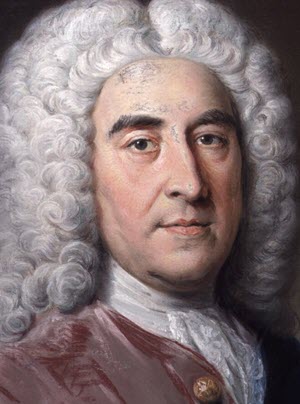

| 12 | 1742 | - 16 Feb 1742—27 Jul 1743: Earl of Wilmington - 2nd British Prime Minister

Spencer Compton, 1st Earl of Wilmington, KG, PC was a British Whig statesman who served continuously in government from 1715 until his death. He served as the Prime Minister from 1742 until his death in 1743. He is considered to have been Britain's second Prime Minister, after Sir Robert Walpole, but worked closely with the Secretary of State, Lord Carteret, in order to secure the support of the various factions making up the Government.

|

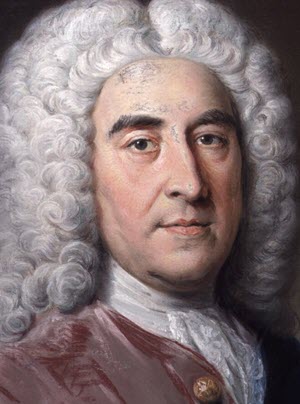

| 13 | 1743 | - 27 Aug 1743—6 Mar 1754: Henry Pelham - 3rd British Prime Minister

Henry Pelham was a British Whig statesman, who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 27 August 1743 until his death.

Pelham's premiership was relatively uneventful in terms of domestic affairs, although it was during his premiership that Great Britain experienced the tumult of the 1745 Jacobite uprising. In foreign affairs, Great Britain fought in several wars. Upon Pelham's death, his brother Newcastle took full control of the ministry.

|

| 14 | 1750 | - 1750: Highland Clearances begin

Highland Clearances: from the 1750s, landlords in the Scottish Highlands began to forcibly remove tenants from their land, usually to replace them with more profitable sheep farming. The clearances resulted in whole Highland communities leaving Scotland and emigrating, most of them to North America. Many others moved to growing urban industrial centres such as Glasgow

- 1750: Sir Joseph Banks born

Sir Joseph Banks was an English naturalist and botanist whose work paved the way for future-botanists. After inheriting a vast family fortune he could chase his passion, and went on to explore previously uncharted territories. He embarked on a voyage with James Cook aboard HMS Endeavour and returned with a major collection of specimens.

Banks advocated British settlement in New South Wales and colonisation of Australia, as well as the establishment of Botany Bay as a place for the reception of convicts, and advised the British government on all Australian matters. He is credited with introducing the eucalyptus, acacia, and the genus named after him, Banksia, to the Western world. Approximately 80 species of plants bear his name.

|

| 15 | 1754 | - 16 Mar 1754—11 Nov 1756: Duke of Newcastle - 4th British Prime Minister

Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne and 1st Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyme, was a British Whig statesman, whose official life extended throughout the Whig supremacy of the 18th century. He is commonly known as the Duke of Newcastle. Historian Harry Dickinson says that he became, "Notorious for his fussiness and fretfulness, his petty jealousies, his reluctance to accept responsibility for his actions, and his inability to pursue any political objective to his own satisfaction or to the nations profit ... Many modern historians have depicted him as the epitome of unredeemed mediocrity and as a veritable buffoon in office."

|

| 16 | 1756 | - 16 Nov 1756—29 Jun 1757: Duke of Devonshire - 5th British Prime Minister

William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, styled Lord Cavendish before 1729 and Marquess of Hartington between 1729 and 1755, was a British Whig statesman and nobleman who was briefly nominal Prime Minister of Great Britain. The Seven Years' War was going badly for Britain under the leadership of the Duke of Newcastle and when he resigned in October 1756, George II eventually asked Devonshire to form an administration. Devonshire accepted on the condition that his tenure would last only until the end of the parliamentary session. Devonshire believed his duty to the King required an administration capable of prosecuting the war successfully.

|

| 17 | 1757 | - 29 Jun 1757—26 May 1762: Duke of Newcastle - 6th British Prime Minister

Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne and 1st Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyme, was a British Whig statesman, whose official life extended throughout the Whig supremacy of the 18th century. He is commonly known as the Duke of Newcastle. Historian Harry Dickinson says that he became, "Notorious for his fussiness and fretfulness, his petty jealousies, his reluctance to accept responsibility for his actions, and his inability to pursue any political objective to his own satisfaction or to the nations profit ... Many modern historians have depicted him as the epitome of unredeemed mediocrity and as a veritable buffoon in office."

|

| 18 | 1760 | - 25 Oct 1760—29 Jan 1820: King George III's reign

George III was the third British monarch of the House of Hanover, but unlike his two predecessors, he was born in Great Britain, spoke English as his first language, and never visited Hanover. His reign was marked by a series of military conflicts involving his kingdoms, much of the rest of Europe, and places farther afield. Early in his reign, Great Britain defeated France in the Seven Years' War, becoming the dominant European power in North America and India. However, many of Britain's American colonies were soon lost in the American War of Independence. Further wars against revolutionary and Napoleonic France from 1793 concluded in the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Later in life, George III had recurrent mental illness. After a final relapse in 1810, a regency was established, and George III's eldest son, George, Prince of Wales, ruled as Prince Regent.

|

| 19 | 1762 | - 26 May 1762—8 Apr 1763: Earl of Bute - 7th British Prime Minister

John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, was a British nobleman who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1762 to 1763 under George III.

Bute's premiership was notable for the negotiation of the Treaty of Paris (1763) which concluded the Seven Years' War. In so doing, Bute had to soften his previous stance in relation to concessions given to France, in that he agreed that the important fisheries in Newfoundland be returned to France without Britain's possession of Guadeloupe in return.

|

| 20 | 1763 | - 16 Apr 1763—10 Jul 1765: George Grenville - 8th British Prime Minister

George Grenville (14 October 1712 – 13 November 1770) was a British Whig statesman who rose to the position of Prime Minister of Great Britain. Grenville was born into an influential political family and first entered Parliament in 1741 as an MP for Buckingham. He emerged as one of Cobham's Cubs, a group of young members of Parliament associated with Lord Cobham.

His government tried to bring public spending under control and pursued an assertive foreign policy. His best known policy is the Stamp Act, a common tax in Great Britain onto the colonies in America, which instigated widespread opposition in Britain's American colonies and was later repealed.

|

| 21 | 1765 | - 13 Jul 1765—30 Jul 1766: Marquess of Rockingham - 9th British Prime Minister

Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, was a British Whig statesman, most notable for his two terms as Prime Minister of Great Britain. He became the patron of many Whigs, known as the Rockingham Whigs, and served as a leading Whig grandee. He served in only two high offices during his lifetime (Prime Minister and Leader of the House of Lords), but was nonetheless very influential during his one and a half years of service.

Rockingham's administration was dominated by the American issue. Rockingham wished for repeal of the Stamp Act 1765 and won a Commons vote on the repeal resolution by 275 to 167 in 1766. However Rockingham also passed the Declaratory Act, which asserted that the British Parliament had the right to legislate for the American colonies in all cases whatsoever.

|

| 22 | 1766 | - 30 Jul 1766—14 Oct 1768: Earl of Chatham - 10th British Prime Minister

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 1708 – 11 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who led the government of Great Britain twice in the middle of the 18th century. Historians call him Pitt of Chatham, or William Pitt the Elder, to distinguish him from his son, William Pitt the Younger, who also was a prime minister. Pitt was also known as The Great Commoner, because of his long-standing refusal to accept a title until 1766.

Pitt is best known as the wartime political leader of Britain in the Seven Years' War, especially for his single-minded devotion to victory over France, a victory which ultimately solidified Britain's dominance over world affairs. He is also known for his popular appeal, his opposition to corruption in government, his support for the colonial position in the run-up to the American War of Independence, his advocacy of British greatness, expansionism and colonialism, and his antagonism toward Britain's chief enemies and rivals for colonial power, Spain and France.

|

| 23 | 1768 | - 1768: Captain James Cook leads his first expedition to the Pacific

James Cook led an expedition on HMS 'Endeavour' to observe the transit of Venus from Tahiti. The voyage continued into the South Pacific, where Cook circumnavigated New Zealand and charted the east coast of Australia. His team of botanists & scientists brought back many important specimens & much scientific information. Cook made 2 further Pacific voyages and was killed on the 2nd of these.

- 14 Oct 1768—28 Jan 1770: Duke of Grafton - 11th British Prime Minister

Augustus Henry FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton, (28 September 1735 – 14 March 1811), styled Earl of Euston between 1747 and 1757, was a British Whig statesman of the Georgian era. He is one of a handful of dukes who have served as Prime Minister.

He became Prime Minister in 1768 at the age of 33, leading the supporters of William Pitt, and was the youngest person to have held the office until the appointment of William Pitt the Younger 15 years later. However, he struggled to demonstrate an ability to counter increasing challenges to Britain's global dominance following the nation's victory in the Seven Years' War. He was widely attacked for allowing France to annex Corsica, and stepped down in 1770, handing over power to Lord North.

|

| 24 | 1770 | - 28 Jan 1770—27 Mar 1782: Lord North 12th British Prime Minister

Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford, (13 April 1732 – 5 August 1792), better known by his courtesy title Lord North, which he used from 1752 to 1790, was Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1770 to 1782. He led Great Britain through most of the American War of Independence. He also held a number of other cabinet posts, including Home Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer.

North's reputation among historians has swung back and forth. It reached its lowest point in the late nineteenth century when he was depicted as a creature of the king and an incompetent who lost the American colonies. In the early twentieth century a revisionism emphasised his strengths in administering the Treasury, handling the House of Commons, and in defending the Church of England.

|

| 25 | 1771 | - 1771: 'Factory Age' begins

The weaving of cotton cloth was a major industry by the 1760s, with most of the labour provided by people in their homes. In 1771, inventor Richard Arkwright opened the first cotton mill at Cromford, Derbyshire. Spinning was carried out by his own patented machine. This was a big step towards the automation of labour-intensive industries and heralded the beginning of the 'Factory Age' in Britain

|

| 26 | 1773 | - 16 Dec 1773: Boston Tea Party

Boston Tea Party: In 1770, taxes on American Colony imports had been repealed on all except tea. In 1773, colonists disguised as Native Americans dumped chests of tea from East India Company ships into Boston harbour in protest against this levy. Tensions between the colonists and the British government escalated.

Back in Britain, the public scoff at the action, because it is common knowledge that for tea to be correctly brewed, the water has to be at boiling point, with milk and sugar added according to taste. However the Boston Tea Party achieved its aims and, to this day, in hotels across America, puzzled British tourists are served "Hot Tea" with water that was boiled sometime in the last couple of hours. To add to their confusion it is served with a slice of lemon instead of milk. Meanwhile their American cousins quaff a strange concoction called "Iced Tea." For this, and this alone, independence was essential to ensure peace and harmony.

|

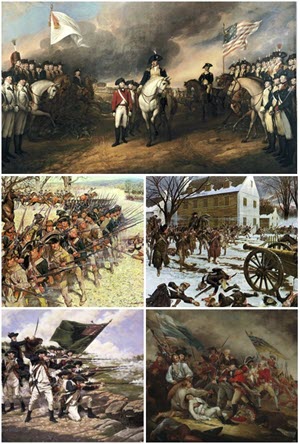

| 27 | 1775 | - 18 Apr 1775—4 Sep 1783: American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War, also known as the American War of Independence, was an 18th-century war between Great Britain and its Thirteen Colonies (allied with France) which declared independence as the United States of America.

After 1765, growing philosophical and political differences strained the relationship between Great Britain and its colonies. Patriot protests against taxation without representation followed the Stamp Act and escalated into boycotts, which culminated in 1773 with the Sons of Liberty destroying a shipment of tea in Boston Harbor. Britain responded by closing Boston Harbor and passing a series of punitive measures against Massachusetts Bay Colony. Massachusetts colonists responded with the Suffolk Resolves, and they established a shadow government which wrested control of the countryside from the Crown. Twelve colonies formed a Continental Congress to coordinate their resistance, establishing committees and conventions that effectively seized power

|

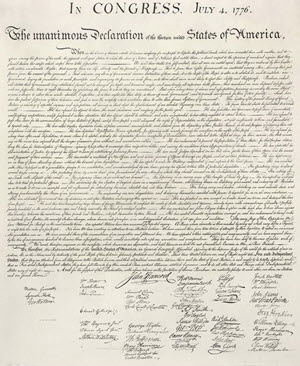

| 28 | 1776 | - 1776: United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence is the statement adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on July 4, 1776. The Declaration announced that the Thirteen Colonies at war with the Kingdom of Great Britain would regard themselves as thirteen independent sovereign states, no longer under British rule. With the Declaration, these new states took a collective first step toward forming the United States of America. The declaration was signed by representatives from New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

|

| 29 | 1778 | - 17 Dec 1778: Sir Humphry Davy born

Sir Humphry Davy, was a Cornish chemist and inventor, who is best remembered today for isolating, using electricity, a series of elements for the first time: potassium and sodium in 1807 and calcium, strontium, barium, magnesium and boron the following year, as well as discovering the elemental nature of chlorine and iodine. He also studied the forces involved in these separations, inventing the new field of electrochemistry. In 1799 Davy experimented with nitrous oxide and became astonished that it made him laugh, so he nicknamed it "laughing gas", and wrote about its potential anaesthetic properties in relieving pain during surgery.

He also invented the Davy lamp which allowed miners to work safely with flame based lamps in the presence of flammable gases. He joked that his assistant Michael Faraday was his greatest discovery.

|

| 30 | 1781 | - 1781: First Iron Bridge

The Iron Bridge is a bridge that crosses the River Severn in Shropshire, England. Opened in 1781, it was the first major bridge in the world to be made of cast iron, and was greatly celebrated after construction owing to its use of the new material.

In 1934 it was designated a Scheduled Ancient Monument and closed to vehicular traffic. Tolls for pedestrians were collected until 1950, when ownership of the bridge was transferred to Shropshire County Council. It now belongs to Telford and Wrekin Borough Council. The bridge, the adjacent settlement of Ironbridge and the Ironbridge Gorge form the UNESCO Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site.

|

| 31 | 1782 | - 27 Mar 1782—1 Jul 1782: Marquess of Rockingham - 13th British Prime Minister

Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, was a British Whig statesman, most notable for his two terms as Prime Minister of Great Britain. He became the patron of many Whigs, known as the Rockingham Whigs, and served as a leading Whig grandee. He served in only two high offices during his lifetime (Prime Minister and Leader of the House of Lords), but was nonetheless very influential during his one and a half years of service.

Rockingham's administration was dominated by the American issue. Rockingham wished for repeal of the Stamp Act 1765 and won a Commons vote on the repeal resolution by 275 to 167 in 1766. However Rockingham also passed the Declaratory Act, which asserted that the British Parliament had the right to legislate for the American colonies in all cases whatsoever.

- 4 Jul 1782—26 Mar 1783: Earl of Shelburne - 14th British Prime Minister

William Petty, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, (2 May 1737 – 7 May 1805), known as The Earl of Shelburne between 1761 and 1784, by which title he is generally known to history, was an Irish-born British Whig statesman who was the first Home Secretary in 1782 and then Prime Minister in 1782–83 during the final months of the American War of Independence. He succeeded in securing peace with America and this feat remains his most notable legacy.

In March 1782 following the downfall of the North Government Shelburne agreed to take office under Lord Rockingham on condition that the King would recognise the United States.

|

| 32 | 1783 | - 2 Apr 1783—18 Dec 1783: Duke of Portland - 15th British Prime Minister

William Henry Cavendish Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, (14 April 1738 – 30 October 1809) was a British Whig and Tory politician during the late Georgian era. He served twice as British prime minister, of Great Britain (1783) and then of the United Kingdom (1807–09). The twenty-four years between his two terms as Prime Minister is the longest gap between terms of office of any British prime minister.

During his tenure the Treaty of Paris was signed formally ending the American Revolutionary War. The government was brought down after losing a vote in the House of Lords on its proposed reform of the East India Company after George III had let it be known that any peer voting for this measure would be considered his personal enemy.

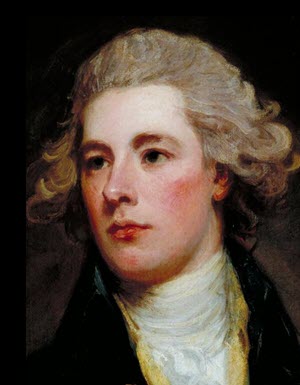

- 19 Dec 1783—14 Mar 1801: William Pitt the Younger - 16th British Prime Minister

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a prominent British Tory statesman of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest British prime minister in 1783 at the age of 24. He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806. He is known as "the Younger" to distinguish him from his father, William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, called William Pitt the Elder or simply "Chatham", who had previously served as Prime Minister.

The younger Pitt's prime ministerial tenure, which came during the reign of George III, was dominated by major events in Europe, including the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Pitt, although often referred to as a Tory, or "new Tory", called himself an "independent Whig" and was generally opposed to the development of a strict partisan political system. He led Britain in the great wars against France and Napoleon. Pitt was an outstanding administrator who worked for efficiency and reform, bringing in a new generation of outstanding administrators.

|

| 33 | 1787 | - 13 May 1787: First fleet of convicts sails to Australia

Since 1718, Britain had transported convicts to its North American colonies, until this was ended by the American War of Independence. On 13 May 1787, penal transportation resumed with a fleet of convict ships from Portsmouth for Botany Bay. This marked the beginning of transportation to Australia. Between 1787 and 1868, when transportation was abolished, over 150,000 felons were exiled to New South Wales, Van Diemen's Land and Western Australia

|

| 34 | 1791 | - 22 Sep 1791: Michael Faraday born

Michael Faraday was a British scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic induction, diamagnetism and electrolysis.

Faraday received little formal education but he was one of the most influential scientists in history. It was his research on the magnetic field around a conductor carrying a direct current that established the basis of the electromagnetic field. He also discovered the principles of electromagnetic induction and diamagnetism, and the laws of electrolysis. His inventions of electromagnetic rotary devices was the basis of electric motor technology, and it was due to his efforts that electricity became practical for use in technology.

As a chemist, Faraday discovered benzene, investigated the clathrate hydrate of chlorine, invented an early form of the Bunsen burner and the system of oxidation numbers, and popularised terminology such as "anode", "cathode", "electrode" and "ion." The SI unit of capacitance is named in his honour: the farad.

- 26 Dec 1791: Charles Babbage born

Charles Babbage was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Considered by some to be a "father of the computer", Babbage is credited with inventing the first mechanical computer that eventually led to more complex electronic designs, though all the essential ideas of modern computers are to be found in Babbage's analytical engine. His varied work in other fields has led him to be described as "pre-eminent" among the many polymaths of his century.

Parts of Babbage's incomplete mechanisms are on display in the Science Museum in London. In 1991, a functioning difference engine was constructed from Babbage's original plans. Built to tolerances achievable in the 19th century, the success of the finished engine indicated that Babbage's machine would have worked.

|

| 35 | 1796 | - 1796: The Vaccine and Discovery of Immunology

Edward Jenner was an English physician and scientist who was the pioneer of smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms "vaccine" and "vaccination" are derived from Variolae vaccinae (smallpox of the cow), the term devised by Jenner to denote cowpox. He used it in 1796 in his "Inquiry into the Variolae vaccinae known as the Cow Pox," in which he described the protective effect of cowpox against smallpox.

Jenner is often called "the father of immunology", and his work is said to have "saved more lives than the work of any other human". In Jenner’s time, smallpox killed around 10 percent of the population, with the number as high as 20 percent in towns and cities where infection spread more easily. In 1821 he was appointed physician extraordinary to King George IV

|

| 36 | 1798 | - 7 Jul 1798—30 Sep 1800: Franco-American War

The Franco-American War more properly known as The Quasi-War was an undeclared war fought almost entirely at sea between the United States and France from 1798 to 1800 which broke-out during the beginning of John Adams' presidency.

After the French crown was overturned during the French Revolutionary Wars, the United States refused to continue repaying its large debt to France, which had supported it during its own revolution. It claimed that the debt had been owed to a previous regime. France was also outraged over the Jay Treaty and that the United States was actively trading with Britain, with whom they were at war. In response France authorized privateers to conduct attacks on American shipping, seizing numerous merchant ships, and ultimately leading the U.S. to retaliate.

|

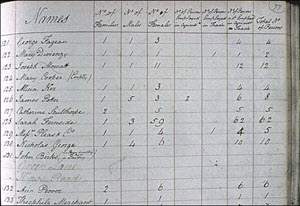

| 37 | 1801 | - 10 Mar 1801: Britain holds First census

Image © Essex University

The census was introduced to help the government understand the country's demographic layout and better utilise the population in wartime. A census of England and Wales, and a separate one of Scotland, has been taken ever since on a ten-yearly basis, with the exception of 1941. In 1801, information was collected on a parish basis. It was not until 1841 that more detailed information was requested.

- 17 Mar 1801—10 May 1804: Henry Addington - 17th British Prime Minister

Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, (30 May 1757 – 15 February 1844) was a British statesman who served as Prime Minister from 1801 to 1804. He is best known for obtaining the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, an unfavourable peace with Napoleonic France which marked the end of the Second Coalition during the French Revolutionary Wars. When that treaty broke down he resumed the war but he was without allies and conducted a relatively weak defensive war, ahead of what would become the War of the Third Coalition. He was forced from office in favour of William Pitt the Younger, who had preceded Addington as Prime Minister.

|

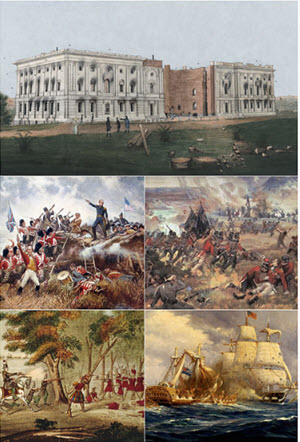

| 38 | 1803 | - 1803—1815: Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of major conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European powers formed into various coalitions, financed and usually led by the United Kingdom. The wars stemmed from the unresolved disputes associated with the French Revolution and its resultant conflict

|

| 39 | 1804 | - 10 May 1804—23 Jan 1806: William Pitt the Younger - 18th British Prime Minister

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a prominent British Tory statesman of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest British prime minister in 1783 at the age of 24. He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806. He is known as "the Younger" to distinguish him from his father, William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, called William Pitt the Elder or simply "Chatham", who had previously served as Prime Minister.

The younger Pitt's prime ministerial tenure, which came during the reign of George III, was dominated by major events in Europe, including the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Pitt, although often referred to as a Tory, or "new Tory", called himself an "independent Whig" and was generally opposed to the development of a strict partisan political system. He led Britain in the great wars against France and Napoleon. Pitt was an outstanding administrator who worked for efficiency and reform, bringing in a new generation of outstanding administrators.

|

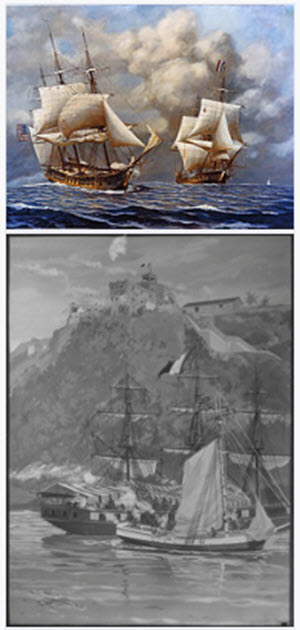

| 40 | 1805 | - 21 Oct 1805: Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar took place between the British Royal Navy amd the fleets of the French & Spanish during the Napoleonic Wars (1796–1815). 27 British ships led by Admiral Lord Nelson on HMS Victory defeated 33 French & Spanish ships under French Admiral Villeneuve. The battle took place in the Atlantic Ocean off the SW coast of Spain, just west of Cape Trafalgar. The Franco-Spanish fleet lost 22 ships, the British lost none

|

| 41 | 1806 | - 11 Feb 1806—25 Mar 1807: Baron Grenville - 19th British Prime Minister

William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, (25 October 1759 – 12 January 1834) was a British Pittite Tory and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1806 to 1807, though he was a supporter of the British Whig Party for the duration of the Napoleonic Wars.

Following Pitt's death in 1806, Grenville became the head of the "Ministry of All the Talents", a coalition between Grenville's supporters, the Foxite Whigs, and the supporters of former Prime Minister Lord Sidmouth, with Grenville as First Lord of the Treasury and Fox as Foreign Secretary as joint leaders. The Ministry ultimately accomplished little, failing either to make peace with France or to accomplish Catholic emancipation (the later attempt resulting in the ministry's dismissal in March, 1807). It did have one significant achievement, however, in the abolition of the slave trade in 1807.

- 9 Apr 1806: Isambard Kingdom Brunel born

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859), was an English mechanical and civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engineering giants", and "one of the greatest figures of the Industrial Revolution, who changed the face of the English landscape with his groundbreaking designs and ingenious constructions". He also had the most outstanding name!

Brunel built dockyards, the Great Western Railway, a series of steamships including the first propeller-driven transatlantic steamship, and numerous important bridges and tunnels. His designs revolutionised public transport and modern engineering.

|

| 42 | 1807 | - 31 Mar 1807—4 Oct 1809: Duke of Portland - 20th British Prime Minister

William Henry Cavendish Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, (14 April 1738 – 30 October 1809) was a British Whig and Tory politician during the late Georgian era. He served twice as British prime minister, of Great Britain (1783) and then of the United Kingdom (1807–09). The twenty-four years between his two terms as Prime Minister is the longest gap between terms of office of any British prime minister.

During his tenure the Treaty of Paris was signed formally ending the American Revolutionary War. The government was brought down after losing a vote in the House of Lords on its proposed reform of the East India Company after George III had let it be known that any peer voting for this measure would be considered his personal enemy.

|

| 43 | 1809 | - 4 Oct 1809—11 May 1812: Spencer Perceval - 21st British Prime Minister

Spencer Perceval (1 November 1762 – 11 May 1812) was a British statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1809 until his assassination in May 1812.[1] Perceval is the only British prime minister to have been murdered. He was also the only Solicitor General or Attorney General to become Prime Minister.

Perceval faced a number of crises during his term in office, including an inquiry into the Walcheren expedition, the madness of King George III, economic depression and Luddite riots. He overcame these crises, successfully pursued the Peninsular War in the face of opposition defeatism, and won the support of the Prince Regent. His position was looking stronger by early 1812, when, in the lobby of the House of Commons, he was assassinated by a merchant with a grievance against his government.

|

| 44 | 1812 | - 1812: Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens is famous for his novels that touch upon the sensitive issues of poverty, child labour, and slavery. During a time when poverty was rife he had the courage to voice his opposition. Most of the characters in his novels are based on people he was acquainted with. This includes his own parents, who were the models for characters Mr & Mrs Micawber in ‘David Copperfield’

- 8 Jun 1812—9 Apr 1827: Earl of Liverpool - 22nd British Prime Minister

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British statesman and Prime Minister (1812–27). As Prime Minister, Liverpool called for repressive measures at domestic level to maintain order after the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. He dealt smoothly with the Prince Regent when King George III was incapacitated. He also steered the country through the period of radicalism and unrest that followed the Napoleonic Wars. He favoured commercial and manufacturing interests as well as the landed interest. He sought a compromise of the heated issue of Catholic emancipation. The revival of the economy strengthened his political position. By the 1820s he was the leader of a reform faction of "Liberal Tories" who lowered the tariff, abolished the death penalty for many offences, and reformed the criminal law.

- 18 Jun 1812—17 Feb 1815: The War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a conflict fought between the United States and the United Kingdom, and their respective allies from June 1812 to February 1815. Historians in Britain often see it as a minor theater of the Napoleonic Wars; in the United States and Canada, it is seen as a war in its own right.

Peace negotiations began in August 1814, and the Treaty of Ghent was signed on December 24. News of the peace did not reach America for some time. Unaware of the treaty, British forces invaded Louisiana and were defeated at the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815. These late victories were viewed by Americans as having restored national honour, leading to the collapse of anti-war sentiment and the beginning of the Era of Good Feelings, a period of national unity. News of the treaty arrived shortly thereafter, halting military operations. The treaty was unanimously ratified by the US Senate on February 17, 1815, ending the war with no boundary changes.

|

| 45 | 1813 | - 1813: Henry Bessemer born

Sir Henry Bessemer was an English inventor, whose steel-making process would become the most important technique for making steel in the nineteenth century for almost one century from 1856 to 1950. He also played a significant role in establishing the town of Sheffield as a major industrial centre.

Bessemer had been trying to reduce the cost of steel-making for military ordnance, and developed his system for blowing air through molten pig iron to remove the impurities. This made steel easier, quicker and cheaper to manufacture, and revolutionized structural engineering. Bessemer also made over 100 other inventions in the fields of iron, steel and glass and profited financially from their success.

|

| 46 | 1815 | - Mar 1815: Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and trade restrictions on imported food and grain ("corn") enforced in Great Britain between 1815 and 1846. They were designed to keep grain prices high to favour domestic producers and imposed steep import duties, making it too expensive to import grain from abroad, even when food supplies were short.

The laws became the focus of opposition from urban groups who had far less political power than rural Britain. The Irish famine of 1845–1852 forced a resolution because of the urgent need for new food supplies. Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, a Conservative, achieved repeal with the support of the Whigs in Parliament, overcoming the opposition of most of his own party.

- 17 Jun 1815—5 Dec 1815: Second Barbary War

The Second Barbary War (1815) was fought between the United States and the North African Barbary Coast states of Tripoli, Tunis, and Ottoman Algeria. The war ended when the United States Senate ratified Commodore Stephen Decatur’s Algerian treaty on December 5, 1815. However, Dey Omar Agha of Algeria repudiated the US treaty, refused to accept the terms of peace that had been ratified by the Congress of Vienna, and threatened the lives of all Christian inhabitants of Algiers. William Shaler was the US commissioner in Algiers who had negotiated alongside Decatur, but he had to flee aboard British vessels and watch rockets and cannon shot fly over his house "like hail" during the Bombardment of Algiers (1816). He negotiated a new treaty in 1816 which was not ratified by the Senate until February 11, 1822 because of an oversight.

- 18 Jun 1815: Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought near Waterloo in present-day Belgium. A French army under the command of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte was defeated by two of the armies of the Seventh Coalition: a British-led Allied army under the command of the Duke of Wellington, and a Prussian army under the command of Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Prince of Wahlstatt. The battle marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars

- 10 Dec 1815: Ada Lovelace born

Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace (née Byron) was an English mathematician and writer, known for her work on Charles Babbage's mechanical general-purpose computer, the Analytical Engine. She was the first to recognise that the machine had applications beyond pure calculation, and published the first algorithm intended to be carried out by such a machine. As a result, she is sometimes regarded as the first to recognise the full potential of a "computing machine" and the first computer programmer.

Lovelace was the only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron and his wife Anne Isabella "Annabella" Milbanke, Lady Wentworth. Ada translated an article by Italian military engineer Luigi Menabrea, on the Babbage engine, supplementing it with a set of notes, which contain what many consider to be the first computer program, an algorithm designed to be carried out on the engine, if it had ever been built.

|