| |

Date |

Event(s) |

| 1 | 1653 | - 16 Dec 1653—3 Sep 1658: Oliver Cromwell's Protectorate

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 1599 – 3 September 1658) was an English military and political leader. He served as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1653 until his death, acting simultaneously as head of state and head of government of the new republic.

Cromwell was one of the signatories of King Charles I's death warrant in 1649. He died from natural causes in 1658 and was buried in Westminster Abbey. The Royalists returned to power along with King Charles II in 1660, and they had his corpse dug up, hung in chains, and beheaded.

|

| 2 | 1657 | - 1657: Edmond Halley born

Edmond Halley was a British astronomer and mathematician, known for calculating the orbit of Halley’s Comet. He went St Helena to make a list of the southern stars. He created a catalogue of 341, which he published as ‘Catalogus Stellarum Australium’. It instantly established him as a leading astronomer, earning him a fellowship at the Royal Society and a M.A. degree from Oxford

|

| 3 | 1658 | - 3 Sep 1658—7 May 1659: Richard Cromwell's Protectorate

Richard Cromwell (4 October 1626 – 12 July 1712) became the second Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland, and was one of only two commoners to become the English head of state, the other being his father, Oliver Cromwell, from whom he inherited the post on his father's death. But but he lacked authority and he formally renounced power nine months after succeeding. Without a king-like figure, such as Oliver Cromwell, as head of state the government lacked coherence and legitimacy.

Although a Royalist revolt was crushed by recalled civil war figure General John Lambert, who then prevented the Rump Parliament from reconvening and created a Committee of Safety, he found his troops melted away in the face of General George Monck's advance from Scotland. Monck then presided over the Restoration of 1660.

|

| 4 | 1660 | - 29 May 1660—6 Feb 1685: King Charles II's reign

After the execution of his father, Prince Charles spent the next nine years in exile in France, the Dutch Republic and the Spanish Netherlands. A political crisis that followed the death of Cromwell in 1658 resulted in the restoration of the monarchy, and Charles was invited to return to Britain. On 29 May 1660, his 30th birthday, he was received in London to public acclaim and crowned Charles II. After 1660, all legal documents were dated as if he had succeeded his father as king in 1649.

Charles was one of the most popular and beloved kings of England, known as the Merry Monarch, in reference to both the liveliness and hedonism of his court and the general relief at the return to normality after over a decade of rule by Cromwell and the Puritans. Charles's wife, Catherine of Braganza, bore no live children, but Charles acknowledged at least twelve illegitimate children by various mistresses. He was succeeded by his brother James

|

| 5 | 1665 | - 1665—1666: Great Plague of London

Although the Black Death and had been known in England for centuries, the Great Plague killed an estimated 100,000 people - almost a quarter of London's population - in 18 months. King Charles II and his court left London and fled to Oxford.

At that time, bubonic plague was a much feared disease but its cause was not understood. Some blamed emanations from the earth, "pestilential effluviums", unusual weather, sickness in livestock, abnormal behaviour of animals or an increase in the numbers of moles, frogs, mice or flies. It was not until 1894 that the identification by Alexandre Yersin of its causal agent Yersinia pestis was made and the transmission of the bacterium by rat fleas became known.

|

| 6 | 1666 | - 2 Sep 1666—5 Sep 1666: Great Fire of London

The people of London who had managed to survive the Great Plague of the previous year must have thought that 1666 could only be better, then on 2 September in a bakery near London Bridge, a fire started … the Great Fire of London.

The fire gutted the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall. It threatened but did not reach the aristocratic district of Westminster, Charles II's Palace of Whitehall, and most of the suburban slums. It consumed 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, St Paul's Cathedral, and most of the buildings of the City authorities. It is estimated to have destroyed the homes of 70,000 of the City's 80,000 inhabitants.

The death toll is unknown but was thought to be small, as only six verified deaths were recorded. This has recently been challenged because the deaths of poor and middle-class people were not recorded; moreover, the heat of the fire may have cremated many victims, leaving no recognisable remains.

|

| 7 | 1685 | - 6 Feb 1685—23 Dec 1688: King James II's reign

James II of England and Ireland, and James VII of Scotland reigned from 6 February 1685 until he was deposed in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He was the last Roman Catholic monarch of England, Scotland and Ireland.

The second surviving son of Charles I, he ascended the throne upon the death of his brother, Charles II. Members of Britain's Protestant political elite suspected him of being pro-French and pro-Catholic and of having designs on becoming an absolute monarch. When he produced a Catholic heir, a son called James, leading nobles called on his Protestant son-in-law and nephew William III of Orange to invade, which he did in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. James fled England. He was replaced by his Protestant daughter Mary. James made one serious attempt to recover his crowns from William and Mary when he landed in Ireland in 1689. After the defeat of the Jacobite forces by the Williamites at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, James returned to France.

|

| 8 | 1689 | - 13 Feb 1689—8 Mar 1702: King William III's reign

William III, supported by a group of influential British political and religious leaders, invaded England in what became known as the "Glorious Revolution," landing at the southern English port of Brixham. James was deposed and William and his wife became joint sovereigns. William and Mary reigned together until Mary's death on 28 December 1694, after which William ruled as sole monarch.

William's reputation as a staunch Protestant enabled him to take power in Britain when many were fearful of a revival of Catholicism. Hiss victory at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 is still commemorated by loyalists in Northern Ireland and Scotland. His reign marked the beginning of the transition from the personal rule of the Stuarts to a more Parliament-centred rule

- 13 Feb 1689—28 Dec 1694: Queen Mary II's reign

Mary II (30 April 1662 – 28 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, reigning with her husband, King William III of England and Ireland, and King William II of Scotland. William and Mary, both Protestants, became king and queen after the Glorious Revolution, which resulted in the adoption of the English Bill of Rights and the deposition of her Roman Catholic father, James II and VII. William became sole ruler upon her death in 1694.

Mary wielded less power than William when he was in England, ceding most of her authority to him, though he heavily relied on her. She acted alone when William was engaged in military campaigns abroad, proving herself to be a powerful, firm, and effective ruler.

|

| 9 | 1702 | - 8 Mar 1702—1 Aug 1714: Queen Anne's reign

Queen Anne, the second daughter of James II, Anne was a staunch, high church Protestant. During her reign Britain became a major military power and the foundations were laid for the 18th century’s Golden Age.

Anne was plagued by ill health throughout her life, and from her thirties, she grew increasingly ill and obese. Despite seventeen pregnancies by her husband, Prince George of Denmark, she died without surviving issue and was the last monarch of the House of Stuart. Under the Act of Settlement 1701, which excluded all Catholics, she was succeeded by her second cousin George I of the House of Hanover.

|

| 10 | 1704 | - 4 Aug 1704: Gibraltar captured

Anglo-Dutch forces captured Gibraltar from Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession on behalf of the Habsburg claim to the Spanish throne. The territory was ceded to Great Britain in perpetuity under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. During World War II it was an important base for the Royal Navy as it controlled the entrance and exit to the Mediterranean Sea, which is only 8 miles wide at this naval choke point.

Anglo-Dutch forces captured Gibraltar from Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession on behalf of the Habsburg claim to the Spanish throne. The territory was ceded to Great Britain in perpetuity under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. During World War II it was an important base for the Royal Navy as it controlled the entrance and exit to the Mediterranean Sea, which is only 8 miles wide at this naval choke point.

The sovereignty of Gibraltar is a point of contention in Anglo-Spanish relations because Spain asserts a claim to the territory. Gibraltarians rejected proposals for Spanish sovereignty in a 1967 referendum and, in a 2002 referendum, the idea of shared sovereignty was also rejected.

|

| 11 | 1707 | - 16 Jan 1707: Kingdom of Great Britain founded

Union of England and Scotland. With its economy almost bankrupted following the collapse of the Darien Scheme, a poorly attended Scottish Parliament voted to agree the Union on 16 January

The early years of the unified kingdom were marked by Jacobite risings which ended in defeat for the Stuart cause at Culloden in 1746. In 1763, victory in the Seven Years' War led to the dominance of the British Empire, which was to become the foremost global power for over a century and slowly grew to become the largest empire in history. The Kingdom of Great Britain was replaced by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 1 January 1801 with the Acts of Union 1800

|

| 12 | 1709 | - 1709: Iron making

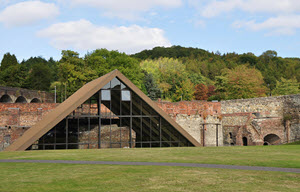

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting.

This is where iron ore was first smelted by Abraham Darby using easily mined "coking coal". The coal was drawn from drift mines in the sides of the valley. As it contained far fewer impurities than normal coal, the iron it produced was of a superior quality. Along with many other industrial developments that were going on in other parts of the country, this discovery was a major factor in the growing industrialisation of Britain, which was to become known as the Industrial Revolution.

|

| 13 | 1714 | - 1 Aug 1714—11 Jun 1727: King George I's reign

George I ascended the British throne as the first monarch of the House of Hanover. Although over 50 Roman Catholics were closer to his predecessor, Anne by primogeniture, the Act of Settlement 1701 prohibited Catholics from inheriting the British throne; George was Anne's closest living Protestant relative. In reaction, Jacobites attempted to depose George and replace him with Anne's Catholic half-brother, James Francis Edward Stuart, but their attempts failed.

During his reign, the powers of the monarchy diminished and Britain began a transition to the modern system of cabinet government led by a prime minister. Towards the end of his reign, actual political power was held by Robert Walpole, now recognised as Britain's first de facto prime minister. George died of a stroke on a trip to his native Hanover, where he was buried - the last British monarch to be buried outside the UK.

|

| 14 | 1718 | - 1718: Transportation of Convicts Begins

The Transportation Act 1717 introduced penal transportation. People convicted of capital crimes had their sentences commuted to 14 years or life in the Americas. Convicts found guilty of non-capital crimes received seven-year sentences. Between 1718 and 1776, over 50,000 convicts were transported to Virginia and Maryland in the modern United States. The American Revolution made further transportation impossible.

|